An Interview with Thomas Cave - Barry Kawa

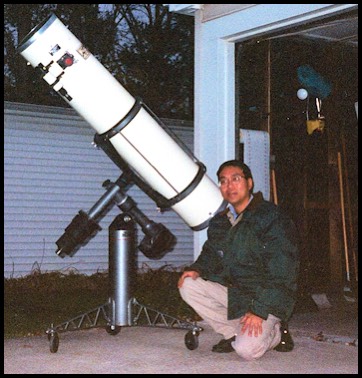

by Barry Kawa

(Special thanks to Astromart.com for making this available)

As a reporter at the Cleveland Plain Dealer in the mid- to late-1990s, I did many of the newspaper’s telescope and astronomy articles, mostly on a freelance basis when I wasn’t covering my usual news and business beat. In the course of those stories, I met a noted astronomy author who asked me if I wanted to join him on a book on the history of commercial telescopes in America. To do it right, I believed I needed to interview the men who made and sold the telescopes, many of whom had long since retired and their companies only distant memories. So, I used my vacation time to track down and travel around the country doing interviews. Some were easier to track down than others. Many were in the phone book. Others were found by asking around and even knocking on addresses of businesses once listed in Sky and Telescope magazine, and asking whoever answered the door if they knew where I could find the previous tenant.

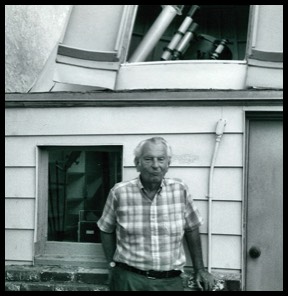

My journey in the summer of 1997 took me to Long Beach, California, to talk to Tom Cave, the founder of Cave Optical Co., at his home there, where he had lived for almost 60 years. I had a 10-inch Cave reflector in my garage in Cleveland Heights that was a pleasure to use and my personal favorite. So, when I called Mr. Cave, it was an honor to speak to him, and he greeted me warmly and invited me out for an interview. I spent a memorable and enjoyable afternoon with Mr. Cave at his home on Roswell Avenue. He was then 74 years old and seemed to enjoy reminiscing and looking back on his company’s history and his interest in planetary observing. Afterward, he showed me his massive 12 ½ inch reflector in his workshop/observatory out back and also his 5-inch Alvin Clark refractor, made in 1868, he was planning to sell.

Sadly, the book I was planning to write with my co-author never materialized. He was busy with other projects, and I would move onto the Dallas Morning News.

All those cassette tapes I used that summer have languished in a box until now. Mr. Cave unfortunately passed away at the age of 80 in 2003. Transcribing the tapes and writing his words in story form, I am glad that his memories of those golden years at Cave Optical Co. will be heard and enjoyed by others.

As he worked as an optician at Herron Optical Co. after returning from a stint in the Army in World War II, a young Thomas Cave decided to start his own optical business. He opened Cave Optical Co. in December 1950 on Anaheim Street in Long Beach, not far from his home, with his father running the business side. At first, Cave didn’t think about making telescopes. The Korean War had broken out that June and there were plenty of government contracts around for a good optical firm, he recalled in an interview at his home almost 50 years later.

The Caves tried land a contract with General Dynamics in Ponomo, a huge optical facility, but they didn’t do any optical work there, just assembly. But the elder Cave knew an Arnold Beckman, who had done business with Herron for years with his company, Beckman Instruments. Cave’s father and Beckman belonged to the same gun club, so he became an important business contact for the new company. The Caves were invited to a party at Beckman’s home a few months after they started their business in 1951. After the party and the banquet, which had about 1,000 guests, they talked business.

The optical work from Beckman helped, then one of the members from the Long Beach Excelsior Telescope Club, who worked at Hughes Aircraft was their vehicle to a lucrative contract, manufacturing thin glass tubes, which were made into resistors for missiles. Cave Optical made them in six or seven lengths, making only pennies apiece on them. But Cave estimated they ended up making some 300,000 of those tubes. “I didn’t know what the hell they were for,” Cave recalled almost 50 years later. But it didn’t matter. For a company that started with little money, those early contracts helped them grow quickly.

The younger Cave finished at USC in late 1951, after attending night school for years on the G.I Bill, getting a degree in design engineering, because the university didn’t offer an optical engineering degree. The only optical degree it offered was in the School of Optometry, which Cave didn’t need. Along with his new business and completing his degree, the younger Cave met the woman he would marry in 1951.

About that time, amateur astronomers starting asking Cave to refigure their mirrors. At first, Cave worked in his garage at home on the mirrors, in his dad’s machine shop, who built some of the company’s first machinery. The Caves also had a friend who had a machine shop, who built some of the first mountings for their optical tubes. Cave had a few patterns made for mirror cells, and he bought focusers from a New York firm at wholesale. At Cave Optical in those days, the shop was only about a mile from their home. The senior Cave. ran the tiny office and the business flourished. The Caves added a machine shop, bought a large and small lathe, a milling machine, added tools and hired a machinist. The elder Cave passed away in 1957, leaving his son on his own.

By the time Cave. sold his company in 1979, he had 35 employees. Cave said they had about 12,000 square feet of space in the shop but always felt cramped.

One of his first mirror makers was Charlie Tarwater, a member of the Excelsior Telescope Club, who had made about a half-dozen mirrors.

One of his other mirror makers was Alika Herring, who had come to California from his native Ohio. Cave offered him $2 more an hour than he was making in a machine shop, plus paid him overtime, which Cave recalls delighted Alika.

In 1959, Herring left Cave to work with Gerard Kuiper at the University of Arizona at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Although Cave built a lot of mirrors for Kuiper, he never met him, one of the few astronomical notables that he never met. “Kuiper was the biggest, square-headed Dutchman on the phone you ever talked to,” Cave said with a twinkle in his eye. “The guy was impossible. He wanted everything the day before he ordered it.”

Cave Optical specialized in long-focus Newtonians. Cave was the rare combination of being equally skillful as an observer and optician. Since Cave loved the planets - particularly Mars - it’s no mystery why Cave telescopes were designed for high-power planetary viewing. “The thing I always said, if a guy wanted to do planetary work, I always told them, ever since I was kid—since my first 6-inch F-10—to get a long-focus F-9, F-10 or F-11,” Cave said. Cave’s prowess at planetary observing even impressed professional astronomers. In 1941, when he was 18, he sent one of his Mars sketches to Lowell Observatory, where E.C. Slipher, a staff astronomer there, recognized Cave’s talent. Slipher wrote to Cave asking him how long he had been observing Mars. Cave wrote back about his background, and that he had made 256 drawings of Mars in 1941 while he was working at Herron Optical.

Slipher offered Cave a job, though on the observatory’s limited budget, the pay wouldn’t be good. The offer was to be Slipher’s personal assistant on the study of the brighter planets, particularly Mars. “I was nutty about Mars,” Cave said, some 56 years later, looking back. “I had to wring my hands for a long time over that, for about two to three days. My father said, ‘Don’t you dare do that.’ He said, ‘You stay at Herron’s and get a profession you can count on.’ “

Cave wryly noted that, today, you can’t count on a precision optical job anymore. But he had no regrets about not taking the position, saying that he would have needed more than a bachelor’s degree to be a professional astronomer.

At Cave Optical, the company advertised its business in the Yellow Pages and Sky and Telescope magazine and had a prominent store front in Long Beach, and business boomed. Cave admitted that his company always had more orders than it could handle and always fell behind. In those days, Cave could look to an East Coast rival to help him out. Although a continent away, John Krewalk Sr. at Criterion Mfg. Inc. of Hartford, Conn., another top-quality Newtonian telescope manufacturer, became his good friend. Cave recalled Krewalk visiting him when brought his family out to visit Disneyland. The Krewalk family would stay at the Disneyland Hotel, and they would stop by Cave’s home in nearby Long Beach, and Cave would stop by their suite. “I thought a lot of them, I liked John Sr. really well,” Cave smiled. Cave said he thought the world of John Krewalk Sr. He was saddened when told of Krewalk’s passing on July 15, 1996, at the age of 80, which he did not know about.

“We never were competitors because at Christmas time, he would be way behind, and somebody would call from the Western part of the country and he would refer them to us,” Cave said. “They would come down or call—we got a lot of orders from him, and I did the same thing for him because we were always behind the 8-ball.”

Because of Cave Optical’s close proximity to Hollywood, movie and television stars would invariably drop by the shop. Cave looked as happy talking about those times as he did about his Mars observational work and sketchings. He recalls one of his first famous customers was actress Eleanor Parker, who stopped in and bought an 8-inch F-8 Deluxe model for her husband, a pediatrician.

The next telescope he sold to was to popular actor Richard Widmark, who became a good friend. Widmark became interested in variable star observing and bought an 8-inch Cave reflector. “He was just getting his feet wet in the hobby,” Cave said. “He was a very intellectual sort of fellow.” Cave recalled with a chuckle the time Widmark was on location in Utah shooting a movie with Jimmy Stewart. At home, his teenaged kids threw a party around his swimming pool. Widmark kept his telescope in the swimming pool dressing room. His teenagers took out the telescope to show the moon to other party-goers, and somehow, the telescope ended up at the bottom of the swimming pool. When Widmark returned home, he surveyed the damage done to his beloved telescope. “If those kids were small enough, I would have spanked the hell out of them,” Widmark told Cave.

So, Widmark packed the telescope up in his station wagon and brought it into Cave’s showroom. Cave saw that two of the tripod legs were broken, and the mirror was badly chipped. “He said, ‘Would you give me anything for it?’ I said, ‘Sure, I will give you something for it.’ Widmark then said, ‘I want a 12 1/2 inch Observatory model.”

Cave told him it would take three to five months to make. After finishing the scope, he grabbed one of his workers to help him deliver it to Widmark’s home. An anxious Widmark already had the pier in place. Cave oriented the telescope as close to north as he could, and called Widmark outside to take a look. “He went crazy,” Cave recalled with amusement. “He had us out there all afternoon. The guy was really something.”

Cave’s customers were some of the most famous movie stars of the day. He remember beautiful actress Janet Leigh stopping by in the late 1950s, before she would star in “Psycho,” to buy a 6-inch Deluxe, with a rotating tube, clock drive and setting circles. “She was a real doll,” Cave said admiringly.

He also recalls veteran actor Eddie Albert coming in one day and buying a used 8-inch Newtonian. “Of all the movie people, he was all business,” Cave said. “No laughing, no joking, no small talk, he was all business.” Albert looked around his showroom and saw a reconditioned 8-inch reflector for sale. Cave told him the telescope was priced even higher than a new one, because they were in such high demand. “He said, ‘I’ll take it,’ ” Cave recalled. “He had a Mercedes convertible, and he put the tube in the backseat and the mounting in the trunk. And he just walked off, and I never saw him again in my life.”

In addition to Widmark, Cave made another celebrity friend in Guy Williams, who ironically would later star in the 1960s TV’s science fiction series “Lost in Space.” Williams bought an 8-inch reflector from Cave, then later traded it in toward a 10-inch model. “A big handsome guy,” Cave said of his friend. “I thought he was about 40, and he died down there some years ago in Argentina.”

Another customer Cave thought less of, was comedian Lenny Bruce, who bought a French Bardou brass refractor that a customer had traded in. “He was this dirty mouth comic who was always on drugs,” Cave said. “He was a real nutcase.”

Another star who stopped by on a Saturday in the early 1970s, was someone Cave never will forget. He recalled a big Lincoln Continental, with a spare tire in the back pulled in and parked in his company’s large parking lot. “This guy comes in, he had yachting denims and a yachting cap on, and it was John Wayne and he was looking for his son,” Cave recalled. Wayne’s son was a good friend of Bob Crawford, one of his top mirror makers. “He was a whopping guy – he must have been 6 foot 5 ½ or something,” Cave said of the Duke. “This was long before he got the bad cancer. God, he smoked one cigarette after another for two or three hours there. I took him all through the shop, he was very pleasant when I got to know him.”

Cave estimated that his company made thousands of complete telescopes over the years, and built some 83,000 primary mirrors, with about 1,000 or 2,000 of them going to the aerospace industry. Some went to NASA, some to Hughes Aircraft and some to foreign governments. Cave said the biggest mirror his company made was a 36-inch one for the Mexican Defense Ministry, who sent their employees to talk to him. “They had some of the sharpest optical men I ever met,” he said. “They came up and spoke good English. They were very high-caliber engineers.”

Cave said he tested every mirror that left his shop. He would also make the trip once or twice a week to take the finished mirrors to be coated at Los Angeles outfit, the name of which he couldn’t recall. Among of his mirror makers, Herring is the most celebrated. But Cave snorted when asked if he was his best. “Herring wasn’t even my best optician,” he said. “Herring used to blow his horn so loud you could hear it even in Europe.” In the shop at Cave Optical, there was a rule that no one put their name on the back of a mirror. The mirror makers used a diamond scribe to inscribe the serial number, focal length and date. He said with a laugh that Herring ignored that “rule” and would put his name on the back of the mirror or side of the mirror.

What was also particularly irksome to Cave was that he would get long-distance calls over the years asking if Herring made their mirrors. “I say, ‘I don’t know, but there were seven or eight more people who worked on them,’ “ he said. “So it could be anyone’s mirror. They were all pretty good. I tested every one of them myself.” What about a story in Sky and Telescope magazine that said that the mirror in Cave’s personal telescope was made by Herring?

Cave looked puzzled. “I never had a Herring mirror in my life he made for me,” he said. “Herring made a mirror for himself at the shop. After hours, he figured that thing before he went to Kuiper’s school in Tucson. It was an exceptionally fine mirror. Probably the best thing he ever did in his life of that size. And he used it to test the seeing for Kuiper.”

Cave said his best optician was a former Merchant Marine sailor named Richard Wheatman, who later went to work for Parks Optical. He said Wheatman lived about two blocks from the shop and one day, he came in to buy a 6-inch F-8 mirror. He later returned to buy eyepieces and asked if Cave was looking to hire anyone. Cave put him to work in the machine shop, but he noticed that Wheatman on his breaks was always talking to the opticians. “I asked Dick, ‘Would you like to try your hand at it?’ And he said, ‘I would love to.’ He had a natural talent for it like you never saw,” he said.

Cave also mentioned Ed Beck, Walter Depampalis and Bob Crawford as his standout opticians. His first mirror maker was Charlie Tarwater, a member of the Excelsior Telescope Club, who died in 1956 of lymphatic cancer. “If he had lived and been in good health he would have been as good as Dick Wheatman,” Cave said. “He could make mirrors but he was such a perfectionist. And he was fast.”

In addition to Newtonians, Cave made cassegrains and refractors. Cave estimated that his company made about 200 refractors, making all the 6-inch lenses in house. The 4-inch objectives they purchased from A. Jaegers of Lynbrook, New York. Their largest refractor was a 13 ¾ inch refractor they made for the British government that was destined to be used as an eclipse expedition telescope in the Far East. “It was a peach, too,” Cave enthused. He said the Royal Air Force flew into Long Beach and the service members in uniform came by the shop to pick it up and fly it back to Britain.

One trend over the years bothered Cave. Customers increasingly requested shorter focal length mirrors, in keeping with the Dobsonian telescope revolution that rose up during the later years of his company. “The longer I was in business, the shorter the focal lengths got,” Cave said. “I got really ticked off about it.”

In addition to Cave-badged scopes, Cave sold other telescopes in the big showroom up front. At the Cave showroom, customers could find other things for sale, such as Swift spotting scopes and every once in a while, a used Fecker or other World War II spotting scope. Cave also sold Nikon refractors, which he called “superb” and considered of the highest quality.

But for the price, he was also impressed with an imported 60mm Japanese refractor that were called Akron. He recalled buying 200 or 300 before every Christmas because parents would come in wanting to get a small telescope for their child, and the Akron was perfect. He estimates that Cave Optical sold about 1,000 of those little Akron refractors over the years, with most finding a home under Christmas trees in homes around Southern California. “Optically, they were just superb,” Cave marveled.

Cave said business was fine up until the beginning of the end, in March 1979, when he came down with a bad fever. Cave had suffered from kidney stones from the time he was in his late 20s. This time, he was in the hospital for about six weeks and running a fever of about 105 degrees. Finally, doctors discovered a large kidney stone blocking the passage of urine. Recovery was slow. “My wife said to me, ‘You keep lying to your customers. You say it will take two months, but you take three months. I said, ‘You got to go out there and run it for me. I was in the hospital for 60 days.”

During his hospital stay, Cave said that Meade Instruments Corp. hired away two of his best machinists and four of his best opticians. “He stole them all away from me by paying them a lot more money down in Costa Mesa,” Cave fumed. “And boy was I mad when I got out and found out about this.”

Cave was warned by his doctor that he might die if he tried to run his company without a backup person to help out, and urged him to sell. So, Cave retained a broker in Santa Monica who found a couple of Britons who were buying struggling companies like his, and willing to take over his company.

Later, Cave, his optical skills in demand, would run the small optical facility at Hughes Aircraft, then Perkin-Elmer before retiring in 1988 to return to his beloved planetary observing. Even in 1997, Cave had about 50 pyrex, zerodur and quartz blanks in his possession and was planning to make mirrors, because people out there still wanted the best. “I’ve got some 30 people in ALPO (The Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers) that want me to make them long-focus mirrors,” Cave said. “Supposedly 8s and 10s. I’m not wild about doing 12 ½ ones anymore. But I will do them, if somebody wants one.”

-Barry Kawa